COVID-19 has brought misery, tensions and deep fissures in its wake. As President Trump continues to exploit the deep underlying strains in the sociopolitical landscape, the country has exploded with anger, frustration and a growing loss of hope and confidence in national and local leaderships. It is difficult to imagine that issues other than the momentous protests against anti-black police violence and anxieties about the fast approaching elections could generate more conflicts. But in many communities, the question of school reopening has become a particularly fractious issue.

In fact, this is not surprising. Families have been struggling to cope for months with the effect of the nationwide shutdown of educational institutions, after-school activities, summer camps and children’s programming. With unemployment rates at a level not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s, our precarious sense of human security has been further assaulted. The data shows severe hikes in domestic and intimate partner violence, depression and other mental health problems, use of alcohol and illegal drugs. As human rights advocates, many of us are concerned about the overall wellbeing of vulnerable children and women who have been isolated in homes and rendered increasingly vulnerable to new forms of abuse.

But school reopening is no panacea, despite the president’s airy call dismissal of the need for masks and demands to re-open the country. Colleges and school districts have struggled with navigating their mission, vision and goals, community needs, policy and process. To add to the messy mix, is a platter of conflicting human rights requirements. We must ask, how do we balance the core rights to the protection of our lives, health, and an education during a pandemic? There are no easy answers to a question that reflects sharp divides in each community in terms of the needs of diverse students and their families, and of teachers, administrators and other staff members.

I had to confront those dilemmas myself as a college educator and a parent with college kids. When New York state went into lockdown in March, our daughter and nephew came home mid-semester from Princeton and Hamilton hauling what baggage they could retrieve. Thus began the chaos of reorganizing the home space for our newly ‘zoomed” offices and their new virtual classrooms – chemistry, dance, economics and so on. Gated communities sprang up around the house, with nothing to bar entry except the nasty glares and hissed whispers: “I have class” or “I have a meeting”. Our son packed his newly virtual office from Rochester and joined the melee. Gradually, our initial contentment in monitoring their safety at close range (armed with packs of sanitizers and face masks) dissipated. The cathartic frenzied shopping at the start of the lockdown, the collective mourning of the mounting death toll, the fears as a sibling, an aunt, uncle and a cousin battled through COVID illnesses gave way to angst felt by millions of parents dreaming of school re-opening. Just five months of shutdown, and we were beset with parental hopes that somehow their colleges would find a way to assume the task, in loco parentis, of joyfully shepherding them to the safe shores of a post-COVID era.

At the same time, perhaps hypocritically, I was engaged in conversations on all the many reasons why my institution, Ithaca College (IC), would probably be unable to resume in-person instruction in the Fall. The anxiety of administration to make it happen, and the herculean efforts of myriad faculty and staff who spent the entire summer working through every possible obstacle did not prevent the undercurrents of contrary reasoning and the growing recognition of the enormity of the challenges and risks involved. Tensions certainly escalated during college meetings amidst pointed complaints about the lack of “trust’ in college management and administrative angst about faculty pushback.

At a personal level, despite missing the students and the power of our pedagogies that depended on in-person conversations and encounters, like numerous other faculty, I had to consider my health conditions that placed me at high risk for in-person instruction. Like dominoes, multiple institutions, Harvard, California State Universities, Bowdoin etc., canceled plans for in-person instruction; while others like Howard, Georgetown, George Washington, American and Ithaca College, reversed previously announced plans to bring undergraduate students to campus. Some of those that pushed full-steam ahead faced startling explosions in COVID cases leading to abrupt shutdowns of campuses like SUNY Oneonta and the University of North Carolina, while others like our neighboring Cornell, appear to be doing relatively and enviously well.

On the Human rights implications of sending children back to school during a pandemic, Amy Maguire and Donna McNamara note that in even in Australia, with its relatively low COVID counts, the debates about a return to classroom learning have been fraught with tensions. The Ithaca school district, despite (and perhaps because of) the city’s extremely low COVID exposure rates, is no less fraught with controversy and divides. A district administered survey had apparently revealed that the numbers of student-families wishing to return to in-person instruction was almost twice the number of teachers willing to teach in-person. Such an outcome illuminates the conflict around negotiating human rights in this context. It also explains the strong reactions to the district’s policy reversal on permitting teachers (but not other staff) a choice of virtual vs in-person teaching. With less than two weeks to the announced transition from virtual instruction to various forms of hybrid teaching, it was not surprising that strong undercurrents of anger, anxiety and oppositional stances surged to the fore in the community.

Winning Assent, Stifling Dissent

While the school district leadership cannot set itself the task of pleasing every constituent or meeting the needs of each individual, staff member and family, I do hope it will take on the challenge of responding differently and more positively to legitimate policy concerns and discussions from various segments of the community.

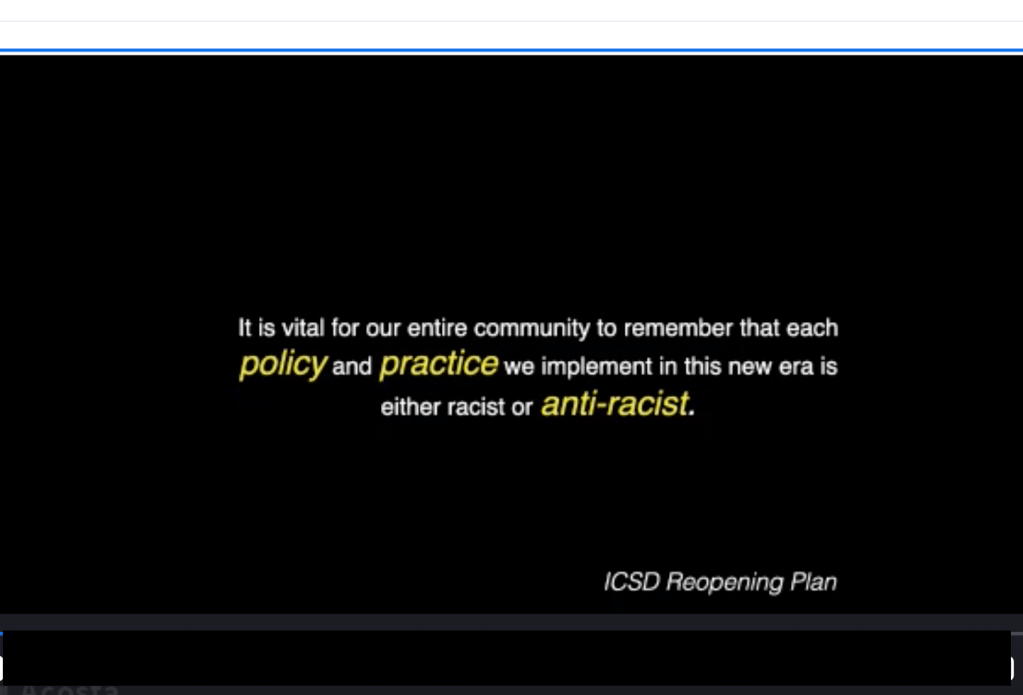

During District Superintendent Brown’s address to ICSD staff during its Fall convocation, he identified the discrepancy between the 60% of families looking for in-person instruction vs the 30% of teachers willing to do so as a factor in his need to revisit the promise of “instructional mode choice” for school reopening. No doubt, the decision was a tough one, one that must have involved multiple deliberations on what was at stake. I personally spoke with Dr. Snedeker, a notable local pediatrician and advocate for children who helped the school Board think through the specific implications for children on being at home for a prolonged period of time. Dr. Snedeker’s careful reasoning around the optimal context for children’s schooling -if community spread remains low ― was not meant to exclude consideration of the needs and rights of staff and families, or to silence those in situations that require them to restrict in-person contact. Perhaps it might have been helpful if his actual comments were fully relayed to the ICSD convocation with their appropriate caveats. Rather, the district superintendent ultimately chose to frame his most passionate defense around the notion he emblazoned on a slide.

Such nods to anti-racist struggles can be a genuine commitment, but when foisted into policy decisions around the resolution of competing legitimate rights and serious health needs, they may serve, intentionally or inadvertently, to redirect the discourse, silence opposition and delegitimize rational opposing claims.

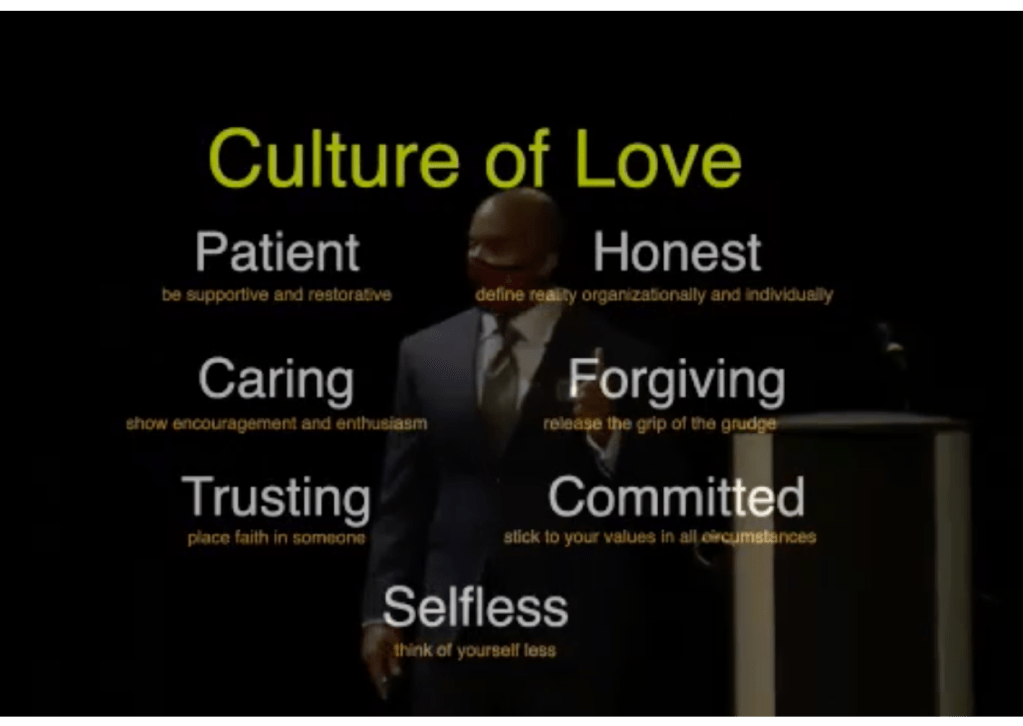

At the least, it seems the superintendent and school Board missed a critical chance to allay the legitimate concerns of teachers and other staff members who needed to hear a coherent medically framed reasoning and discussion of key considerations undergirding the move toward requiring in-person teaching (with exceptions for approved medical conditions). Indeed, many of the concerns raised by teachers have been acknowledged and highlighted by the Inter-Agency Network on Education in Emergencies. With that in mind, it is unfortunate that the superintendent’s address seemed to characterize such teachers as lacking enough love for their students, or as adults unwilling to be “uncomfortable and to struggle” in order to “meet the needs of our learners” through an “authentic” journey and culture of love.

In the journey to survive COVID as a community, we must be cautious about the weaponization of language. Defensive postures by those in authority may result in various forms of preemptive gaslighting that silence and control healthy dissent. When a leadership accuses its constituents of “lack of trust,” such allegations distort the nature and value of sociopolitical trust and crush conversation on how to negotiate competing needs. Certainly, there are forms of puerile, self-serving, and ignorant opposition that may denigrate the innocent, inflame tempers and cast suspicion on expedient choices and programs. The specter of national political leaders who disparage the use of masks, and question climate change as ‘fake news’ is testament to dangerous dissent.

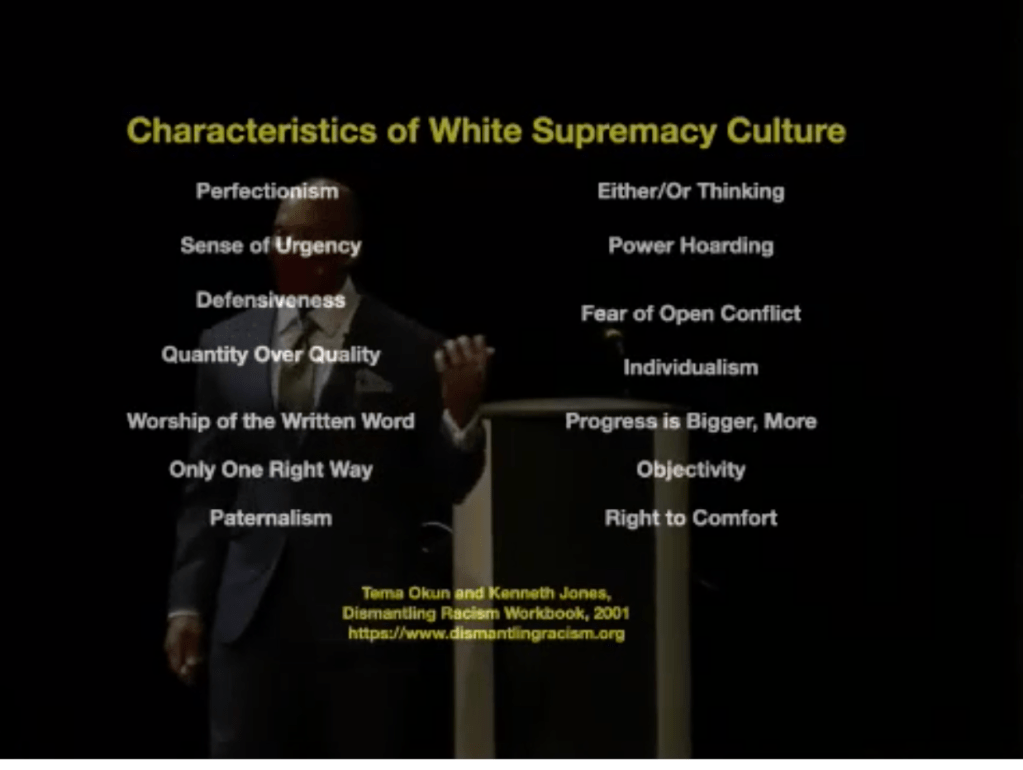

But if we wish to to build a community where language does not become a cudgel that bludgeons dissenters into submission, local leaders must also be wary of the temptation to deploy simplistic characterizations and imaginaries of the camp of the “Other”. Teachers, staff and students do have legitimate and anxious questions about pandemic-era in-person learning modules. Such concerns should not be mischaracterized as dastardly weapons launched from the camp of the elitist, entitled, racist, virtual home-schoolers, against the under-served, needy, marginalized, hard working underclass folks eager for in-person instruction. When a District Superintendent of Schools offers a background of slides that appear to imagine all critics of school policy as patriots of white supremacist spaces, such notions rapidly morph, and dangerously so. They conjure and harden stereotypes of the other, strangulate meaningful discussions of policy, and accelerate community fracture. Conflicts are inescapable in the “long walk” to change, but hopefully they will emerge from substantive issues, not diversionary and politically manufactured divides.

The district must understand that the task of balancing stakeholder rights to health protection as well as student learning, will generate unfortunate outcomes for many. Those outcomes are significant and those affected should not be countered with the barbed arrows of guilt trips. For when administrators, whether at the college or school district level, employ tools of toxic silencing during their community’s consideration of policy, process and the hierarchy of competing rights, they only stoke up tensions that will smolder into the future.

It seems disingenuous for an educational leader to characterize concerns about health and safety as being antithetical to the “authentic journey”. It is equally problematic to reduce concerns about the health consequences of teaching in person during a pandemic to folks “getting mad” simply because they are embedded in and supposedly wedded to the characteristics of white supremacist culture as opposed to the “culture of love”, which presumably demands sacrificial risk-taking and self-abnegation.

At a time when the dilemmas and debates about school reopening are being enacted in other countries and communities around the world, local school districts should embrace the chance to respond in a reasoned and logical manner regarding the negotiation of conflicting but equally legitimate rights. Dr. Brown states at the September ICSD convocation that “what I know is that no superintendent who has engaged in this conversation has survived it. Typically, they find some reason for you not to be there no more… you are making too much money; you drive too fancy of a car; or they create some other of a controversy; just do a google search on superintendents who talk about equity and antiracism- you will see what happens. But I can tell you right now, this authentic journey I am on, that I promised my mama I would stay on is where I am going to be.”

His words of course cast a strange glow of heroic and imminent danger of death by political assassins. It would possibly have been more persuasive if this was the first year of the superintendent’s public voicing of anti-racist sentiments, rather than what is in fact, the eleventh year of his term in office and reiteration of the same discourse. Ithaca of course is hardly as liberal, progressive or radical as it pretends to be. However, since the superintendent has managed to survive and thrive despite holding the same anti-racist “conversations” year after year, one must wonder what purpose his words were intended to serve. They did seem to have inspired a rousing round of applause by an enthused group of listeners, as well as muted oppositional responses. Overall, in my opinion, he seemed to douse what could have been a thoughtful, vibrant ICSD conversation that might have even generated empathy, and support for the district’s COVID policy dilemmas and decisions. It is certainly disappointing to witness a misdirection of the conversation in a public statement that suggests criticisms are merely emanating from a malicious intent to destroy the careers of progressive and anti-racist educational administrators.

The cost of such preemptive mobilization and silencing by an educational leader is high, perhaps too high. Sadly, his claims also obscures the thousands of courageous leaders across the nation who have accomplished some enviable victories in transforming educational spaces. Many of them, of course, paid a heavy price for their involvement in anti-racist and equity struggles to transform educational systems particularly in deep conservative and racist enclaves. In one news item, 33 district superintendents cemented their struggles with a public stance against racism, others have issued public statements documenting their position and battled their school boards in order to build a system geared toward lasting change.

It might be the prerogative of any leader to issue forewarnings about conspiracies to dethrone them for ostensibly having too much money, fancy cars, or other “created” or trumped up controversies, but it is important to note the fallacies and dangers of issuing such warnings as a response to policy discussions, particularly when the concerns being debated are currently also being discussed across the nation and world.

The preemptive flattening of school districts and colleges into racist vs anti-racist, for me/against me camps, can spiral into a toxic community fracture that loses sight of the actual issues at stake. The imagined dual worlds comprising “authentic” voyagers supportive of in-person instruction versus an oppositional self-serving racist white supremacist academic camp ignores and renders invisible the truth of our complicated communal landscape. In reality, our community landscape features cross-cutting anxieties, concerns, restrictions and needs that are focused on issues of health, student and staff wellness, unique domestic situations impacted by COVID, and hardly simply about a superintendent’s fancy car, or wealth. Such voices and questions should not be designated as malicious, neither should they be met by irate and punitive responses that shut down critical conversations.

The district superintendent has offered teachers a list of antidotes for “dismantling white supremacist culture”, including trust, lack of defensiveness, honesty and patience. More than ever, this is the time for administrative leaders themselves to actually engage those qualities in engaging their constituencies, perhaps discovering in the process that thoughtful critics can be more valuable than an army of muted loyalists.

Peyi Soyinka-Airewele

Peyi is Professor of Politics at Ithaca College, NY & member of the Tompkins County Human Rights Commission. Opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not represent the commission or other agencies with which I am affiliated.